Formal teacher evaluations are one of the most important and time-consuming responsibilities principals and assistant principals face each year.

In this article, we'll discuss a set of strategies that can help you write dramatically better evaluations in less time.

One reason it can be time-consuming and overwhelming to write evaluations is that they're often expected to accomplish a wide range of goals, such as:

These divergent goals can make it difficult to focus your time and effort, so I suggest reducing your priorities for teacher evaluation to just two:

That's what each teacher needs—a clear indication of where they stand, backed by well-reasoned evidence, and followed by the appropriate next steps.

Rather than structure a written final evaluation as a narrative letter—much as you would for a letter of recommendation—it works best to write a GSIR statement for each area of evaluation.

For example, if your evaluation system requires you to evaluate teachers in 4 domains such as Planning & Preparation, Classroom Management, Instructional Skill, and Professional Responsibilities, you would write one carefully-crafted statement for each domain.

As a principal in Seattle Public Schools, I was taught to use the CEIJ format:

I later learned that this acronym comes from the work of Jon Saphier of Research for Better Teaching.

You might also recognize a similarity to the “Claim, Evidence, Reasoning” framework that's often used to teach writing, especially in content areas such as science and social studies.

For teacher evaluations, you might find it helpful to use a variation on this approach, GSIR:

The GSIR format produces tightly argued, well-supported evaluations that will withstand even the closest scrutiny by district administrators, union reps, and attorneys.

Mrs. Smith does not deal effectively with student misconduct, and has failed to establish a classroom climate conducive to learning. As a result, students spend significant time off-task and engaged in conflict. (Generalization)

For example, on 1/31, I observed a brief exchange in which two students exchanged verbal insults, followed by a 15-minute attempt on Mrs. Smith’s part to get the students to ignore each other. During this time, instruction completely stopped, and the conflict was not resolved. In another incident that I observed, on 2/17, three of the five groups spent their group work time arguing over who would do the work, and completed less than half of the assignment in the designated time. (Specifics)

Because Mrs. Smith does not deal with student misbehavior in a timely and authoritative fashion, the classroom environment makes it difficult for students to learn—even students who are attempting to ignore distractions. (Impact)

Therefore, in Domain 2, Classroom Management, Mrs. Smith’s practice is best characterized as Level 1, Unsatisfactory. (Rating)

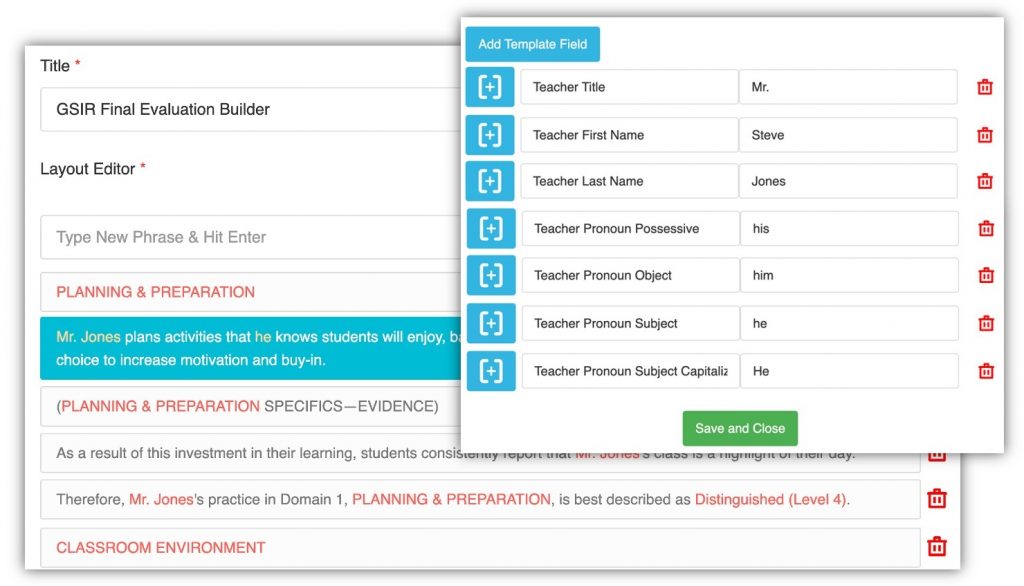

You can write GSIR evaluations quickly using the GSIR Final Evaluation Builder template in Repertoire, the professional writing app for instructional leaders.

How can you write a tightly-argued GSIR statement? Start with your informal impressions, and revise them until they contain each component, in appropriate professional language.

For example, to document classroom management concerns, you might begin with an informal impression:

“Ugh! Mr. Hamm's classroom is so chaotic…things don't flow smoothly because students don't know what to do—or how he wants them to do it.

The next step is to translate your impression into professional language.

For example, your teacher evaluation framework might say “Maintains a safe, orderly classroom environment with well-established routines and procedures to ensure that all students can focus on learning.”

So rather than say the classroom is “chaotic,” you might revise your initial statement to use the language of the evaluation criteria:

“Mr. Hamm's classroom is characterized by frequent disruptions and lost instructional time, stemming from a lack of consistent routines and procedures.”

That's the Generalization, which you could then follow with Specifics:

“For example, in an observation on January 28, seven minutes of class time were spent transitioning between small-group work and whole-class instruction. Students were instructed to move their desks, but did not follow well-rehearsed procedures for doing so.

Then, we can continue using language from the evaluation criteria to identify the Impact:

“As a result, two students were injured by desks being carried in an unsafe manner, and the class ran out of time for the closing activity.”

At this point, the Rating is straightforward:

“Therefore, Mr. Hamm's performance in Domain 2, Classroom Management, is currently at Level 2, Needs Improvement.”

While this example highlights a deficient area of practice, GSIR can be used for any level of performance, from unsatisfactory to exemplary.

Simply use the rating scale, criteria, and terminology of your evaluation system to craft airtight arguments with GSIR.

But how can you know whether your Generalizations fairly characterize the teacher's overall practice?

We don't want to catch teachers at their worst, nor ignore the daily reality in favor of a dog-and-pony show put on for our benefit.

That's why it's so important to get into classrooms frequently, on an informal basis.

Informal classroom walkthroughs may not officially “count” in the teacher evaluation process, but they provide essential context for what you see in formal observations.

The more frequently you're in classrooms, the lower-stakes each visit will be. Teachers will be more relaxed, and won't feel as much pressure to put on a show—so you'll see more typical practice.

For principals who only visit classrooms once a year—for the required formal observation—evaluating teachers fairly is difficult, because formal observations simply don't provide much evidence.

A single observation—perhaps one hour out of more than 1,000 instructional hours in the school year—may produce pages of notes, but it won't show the full range of the teacher's practice.

The key is to combine formal observations with a consistent daily habit of informal classroom walkthroughs.

In Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership, I outline a plan for conducting classroom visits that are:

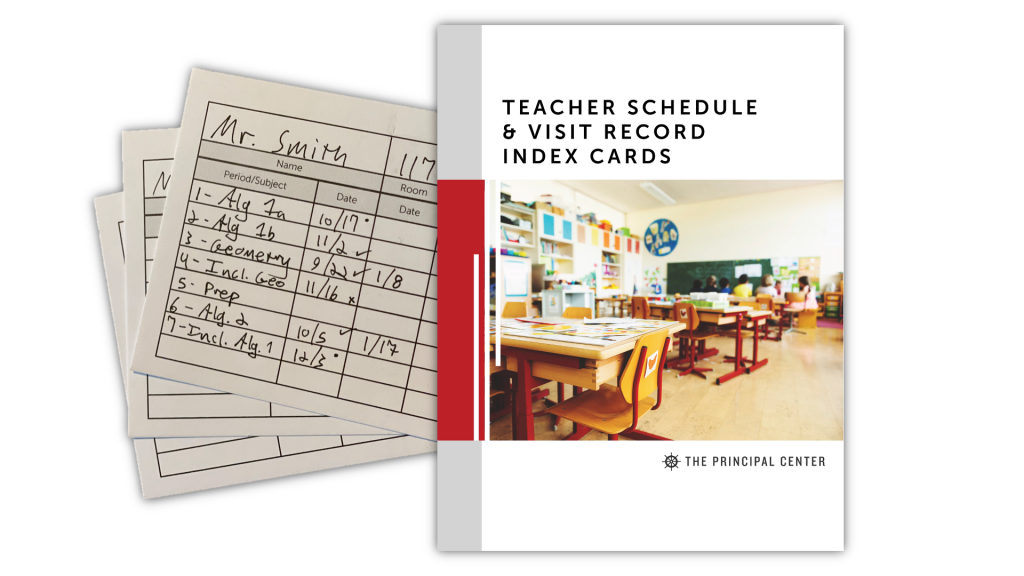

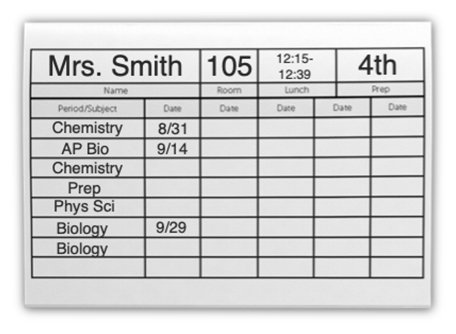

To track your classroom visits, I recommend making a set of notecards—one per teacher—to keep track of your visits.

On each notecard, write the teacher's schedule, so you know what subjects are being taught at what times, and when the teacher has a prep period.

As you see more of each teacher's classroom throughout the year, you'll gradually gain a clearer picture of their practice—and it'll become clear what should go in their evaluation.

Over time, you'll start to notice similarities between teachers, and these similarities can create significant opportunities to save time by re-using your evaluation language.

Once you've written a tightly argued GSIR statement, you've built a tool that you can re-use for other evaluations.

Of the four components, only one—the Specifics—needs to be unique to the teacher and the school year.

If two teacher have similar characteristics in a given domain—or if a teacher's practice stays largely the same from year to year—there's no reason not to reuse your Generalization, Impact, and Rating statements.

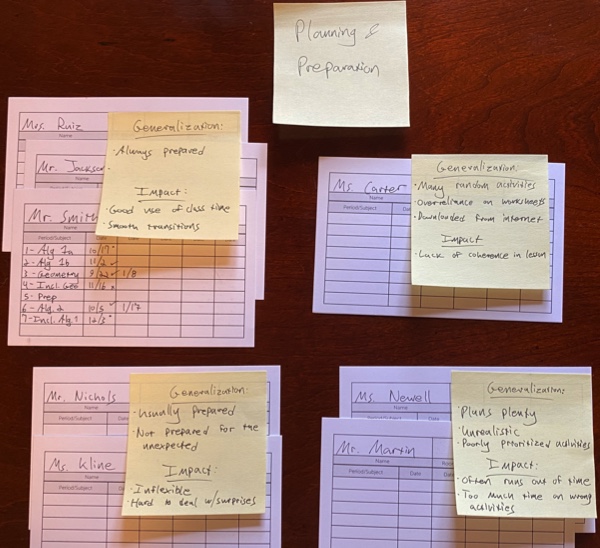

In the Evidence-Driven Teacher Evaluation program, we call this The Bucket Strategy.

An easy way to start is with your notecards and some sticky notes—simply choose an evaluation domain, and start grouping teachers based on similarities in their practice.

For example, in the domain “Planning & Preparation,” you might identify buckets like this:

Bucket #1:

Generalization: Always prepared

Impact: Good use of class time; smooth transitions

Bucket #2:

Generalization: Many random activities; overreliance on worksheets downloaded from internet

Impact: Lack of coherence in lesson

Bucket #3:

Generalization: Usually prepared; not prepared for the unexpected

Impact: Inflexible; hard to deal with surprises

Bucket #4:

Generalization: Plans plenty; unrealistic; poorly prioritized activities

Impact: often runs out of time; too much time on wrong activities

The teachers in each of these buckets are different enough from teachers in the other buckets that it won't work to use the same evaluation language for all of them.

Each bucket will need its own GSIR language—with unique Specifics for each individual teacher, of course.

Once you've written this language for a given bucket, you can re-use it over and over.

Since you'll have several evaluation domains and only one set of notecards, you'll want to record your initial bucket choices somewhere.

To make it easy, I've created an Evaluation Organizer Spreadsheet with customizable domain and bucket names, and dropdown options so you can select a bucket for each teacher in each domain:

Your initial groupings are just drafts, subject to change as you gather more evidence and progress through the later stages of the evaluation process.

If you discover that there are, in fact, major differences between teachers you've grouped in the same bucket, you can create a new bucket, or move teachers to other buckets.

In general, you'll need 3 to 5 buckets for most areas of practice.

A caution: underperforming teachers, who are at risk of a negative evaluation, typically won't fit into any of the existing buckets. They'll need special attention.

Tolstoy's classic novel Anna Karenina begins:

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Effective teachers, too, have a great deal in common with one another, so it's usually possible to describe your entire staff with just 3 to 5 buckets for a given domain of practice.

This introduces a tremendous efficiency in the writing process: by grouping teachers into buckets, and re-using evaluation language for all teachers within a bucket—everything except the specific evidence—we can write low-risk evaluations very quickly.

Underperforming teachers vary much more widely, and typically don't fit into existing buckets in areas where they're struggling.

This brings us to the reason it's so important to re-use good evaluation language once you've written it: doing so will save time that you can re-allocate to high-risk evaluations.

The Pareto Principle, named after famed Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, states that 80% of results come from 20% of inputs, and vice-versa.

Applied to teacher evaluation, this means we can expect to devote 80% of our effort to 20% of our teacher evaluations, while completing the other 80% with just 20% of our total effort.

Let's say you have 30 teachers to evaluate, and you have about an hour to spend on each evaluation, for a total of 30 hours.

Should you spend that time equally on each evaluation? Our egalitarian instinct is to say yes—every teacher deserves the same amount of our time.

But as every teacher knows, strictly equal isn't always fair or best. We need to differentiate, and put our effort where it's most needed.

Many evaluations are low-risk. The teacher will be “satisfactory.” You know it, and they know it. These evaluations can be expedited.

Others are high-risk. We don't know how they'll turn out. HR might get involved. Dismissal and even lawsuits are possibilities. These evaluations deserve great care.

How might we differentiate the amount of time we spend on each evaluation? An 80/20 allocation of 30 hours to 30 evaluations would look like this:

That might seem like an extreme discrepancy, but if you've ever conducted a negative evaluation, you know it's time well-spent.

If you've done a high-risk evaluation, you know 5 hours isn't unreasonable.

If every word you write will be scrutinized by the teacher, the teacher's union rep, the union head, the union attorney, your supervisor, the head of HR, district legal counsel, and the school board…then it's worth putting in the time to get it right.

Meanwhile, as long as low-risk teachers get a fair, well-written evaluation, they don't particularly care whether it took you 15 minutes or five hours.

As much as we might want to spend five hours handcrafting the perfect evaluation for every teacher, time is always tight, and we simply don't have that luxury.

That's why it's so important to prioritize and differentiate. To recap the recommendations above:

What would you add? Leave a comment below and let me know.

Justin Baeder, PhD is Director of The Principal Center, where he helps senior leaders in K-12 organizations build capacity for instructional leadership by helping school leaders:

He holds a PhD in Educational Leadership & Policy from the University of Washington, and is the host of Principal Center Radio, where he interviews education thought leaders.

His book Now We're Talking! 21 Days to High-Performance Instructional Leadership (Solution Tree) is the definitive guide to classroom walkthroughs.